Schizophrenia and Psychedelics in Tripping on Utopia

Connections between altered states in early psychedelic research

For the past several years I’ve suspected that I could be diagnosed with schizophrenia, especially if I was honest with the wrong kind of mental health professional about my writing process. Reading Tripping on Utopia, Benjamin Breen’s alternative history of psychedelic science, brought up schizophrenia again. Schizophrenia appears again and again in the book, adjacent to early researchers’ work in altered states and psychedelics. When I lived in Havre, Montana, where my mother’s family comes from, I met a researcher studying the disorder who came to town because there’s a high incidence rate among Russian Germans on Montana’s Hi Line. Several members of my mother’s family went insane, including my grandfather’s brother who came home from WWI shellshocked, became a drunk and drove into a ditch. A great aunt was taken away to an institution and never spoken of again.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the tool many mental health professionals use to diagnose patients—although most serious ones today will tell you it’s flawed (even the term ‘disorders’ is dated)—schizophrenia is:

- A group of severe mental disorders in which a person has trouble telling the difference between real and unreal experiences, thinking logically, having normal emotional responses to others, and behaving normally in social situations. Symptoms include seeing, hearing, feeling things that are not there, having false ideas about what is taking place or who one is, nonsense speech, unusual behavior, lack of emotion, and social withdrawal.

- A major psychotic disorder characterized by abnormalities in the perception or expression of reality. It affects the cognitive and psychomotor functions. Common clinical signs and symptoms include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking, and retreat from reality.

My mother’s reality never matched the reality outside of our house. Growing up, my two siblings and I spent the majority of our time with her, meaning we picked up her skewed realities. We lived in an idyllic 4-bedroom suburban house with a half-acre garden in Missoula, Montana, and a menagerie of pets. My mother made all of our birthday cakes from scratch, and threw elaborate birthday parties with games for our friends. She once helped me redecorate my room with flowers so I could live with butterflies I brought in from the yard. You might say any little girl would do something like that, it’s just that either I never truly grew up or, since using psychedelics, I’ve regressed back to that state. I just want to live with butterflies and birds. I suppose from the outside it looks as though I’ve retreated from reality, but for me it seems that for the first time in my life I’m paying attention to what’s realest to me. Which are birds and butterflies.

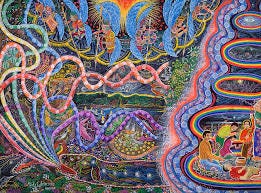

I imagine my former teacher, the shaman, would argue a different cultural perspective, like his Peruvian one, considers schizophrenia, which is believed to affect 0.5 to 1 percent of the population, a gift. I imagine he would point out that many artists exhibit at least some characteristics of the disorder. And I would have to agree.

Schizophrenia and whether psychedelics can be used to understand and treat it emerges as a theme in Benjamin Breen’s alternative history of psychedelic science: Tripping on Utopia. The scientists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson believed trance states, psychedelic states and schizophrenia were linked.

Although not often mentioned by psychedelics advocates today, research into schizophrenia and psychedelics has resumed. This 2023 study published in Molecular Psychiatry said psychedelics could ameliorate “the negative symptoms associated with pathological manifestations” of the disorder but warned, “The foremost concern in treating schizophrenia patients with psychedelic drugs is induction or exacerbation of psychosis.” The study appears to deal with people who had been previously diagnosed with schizophrenia and doesn’t consider whether the disorder can be turned on by psychedelics. Based on personal experience, I believe it can. It’s a side effect I have very rarely heard psychedelic facilitators and advocates discuss. These people often want to distance themselves from anything that could be classified as a disorder in their quest to rebrand psychedelics as substances for mental health, but early researchers knew about the connections and we should be talking about them more today.

Here are some passages on schizophrenia from Tripping on Utopia that discuss early psychedelic science’s preoccupation with the disorder:

- “The center of mescaline research in 1934 was in the Munich lab of Emil Kraepelin, a visionary experimental psychiatrist who had made it his mission to understand the nature of schizophrenia. If psychosis could be mimicked, Kraepelin reasoned, then it could be better understood, and the mescaline experience seemed to him and his lab to be a form of ‘artificial psychosis.’”

- Anthropologist Geoffery Gorer wrote in his 1936 travelogue Bali and Angkor that he “believed the trancelike state induced by mescaline had allowed him to access a mental plane similar to the ‘deliberate delusions’ experienced by Buddhist monks or Balinese trance dancers. Gorer posited that these various altered states were linked, reflecting a common state of consciousness inherent in the human mind---all minds.” Gorer believed everyone could have such schizophrenic experiences.

- To the scientists, “Balinese trance seemed to involve a transformation of identity akin to both schizophrenia and the state induced by peyote,” Breen writes.

- Of the Iatmul people he studied in Papua New Guinea Gregory Bateson wrote, “it is said secretly that men, pigs, trees, grass—all the objects in the world---are only patterns of waves.”

- In 1949 Alan Ginsberg was diagnosed with “schizophrenia—pseudoneurotic type” at Columbia University Hospital. Shortly afterward, he began using psychedelics. Shortly after that, he wrote his most famous poems.

- “The group of eclectic researchers Bateson began to gather around him in 1953 is mostly remembered today in connection with the concept of a ‘double-bind,’ a form of “no-win” situation that Bateson came to believe was related to schizophrenia.” Later Breen writes, “(Bateson) described the double bind as a situation in which a paradoxical communication from an authority figure demands contradictory responses: ‘I cannot survive if I do not obey and to obey would be to die.’ This, he thought, was at least a partial cause of schizophrenia.”

- “Jane Belo, whom Bateson had once been in love with, now suffered from (schizophrenia). The Dallas-born Belo, a dancer turned anthropologist, had always been an unusual person with an extremely vivid imagination. In 1952, she suffered a major episode of depression and checked herself into a mental hospital, where she was given a schizophrenia diagnosis.”

- Bateson wrote about a “constellation of trauma” that forced individuals diagnosed with mental illness into paranoia and withdrawal because their social circumstances made it impossible to communicate effectively with those around them.”

- Bateson emphasized schizophrenia was a result of “communal breakdown” rather than an individual failing.