The Psychedelic English Teacher and the Rez Baller

Coming down from a trip through the psychedelic renaissance

During the summer of 2020, I packed my stuff and moved to Rocky Boy’s Reservation, where I’d gotten a job teaching English. Everything was shut down because of the pandemic, which was ravaging the Rez.

Although I declined to work for the shaman, I still attended his groups, which had migrated to Zoom. He wasn’t very happy about my decision to move to Rocky Boy. He accused me of trying to find “real” indigenous people.

In a way, I was.

And I did.

It turned out most of the real ones I found played basketball.

People in the shaman’s groups seemed very confused about the alleged indigenous roots of psychedelic therapy, and they clung to unfortunate stereotypes of indigenous identity. They promoted anti-vax ideology during the pandemic, and when the shaman, who was himself leery of the vaccine, asked me if I had gotten it, I said that of course I had because I was living in a community in which elders were dying. It was a privilege to avoid the vaccine; it meant you lived in a community and a situation in which multi-generational families under one roof didn’t exist.

More than once in psychedelic groups, I had the truly strange experience of listening to a bunch of white people talk about “sacred indigenous” plant medicine, “indigenous” ways of thinking and “indigenous” ways of life. I think this experience was strange, but it happens all the time in the scene and is probably happening as I write this. Many of these people’s ideas weren’t much different than the stereotypes from the first psychedelic renaissance, except that today indigenous identity, at least as it is defined by white America, has become even more wildly profitable in psychedelics. Every time I hear or see someone in the scene use terms like “indigenous identity” or “indigenous modalities” my response is WTF is that. I don’t think most of them have any idea what they’re talking about.

When I got to the Rez, I was super high on life. While I was on drugs in psychedelic groups, I had been pumped full of ideas about pan-indigeneity that erased more than they illuminated. I knew lots of white people who used the word “Aho” to punctuate their sentences, and others who copied Native American ceremonies like sweat lodges and then charged money to attend them. I wrongly believed, as many of my former journey friends still do, that Native Americans had more access to psychedelic ceremonies than me. I thought my students would already know what I had learned from altered states of consciousness just because they grew up in a Native American community.

Needless to say, the come down at school was rough.

My first year at Rocky Boy the school’s Mormon principal seemed to be on a belated mission trip. He used the intercom profusely, calling the Native American janitorial staff down to his office multiple times a day for meetings. After one of these “meetings,” the janitor who was an Iraq veteran and my friend asked to borrow my lighter. He said he needed to take a smoke break because our boss had just tried to convert him to Mormonism, reading him the Mormon Bible and even tearing up afterward. To the janitor it was funny. He was used to this kind of behavior by white people who come to the Rez. I was horrified. Although the Mormon Missionary Principal was the crassest, I suspect he wasn’t the only member of the staff proselytizing on behalf of Christianity.

The Native American staff joked about the missionary principal, but at least they could sort him, having had decades of experience with his type. I was more difficult to categorize. One of the first times I met him, the blunt Rez baller in my class asked me, “Who are you to us?”

In the moment, I failed to answer him. He has a gift for asking incredibly simple and profoundly disarming questions. Living on the Rez had made him into an expert digger. To this day, he’s the only person I know who can get to the bottom of someone quicker than me. In my teaching career before Rocky Boy, I bragged that I could tease any teenage boy until he shut up, but that kid was different. That kid could slay me.

Every student sitting in my class on the Rez had been deeply affected by the opiate epidemic, including the Rez baller, who had lost his mom to an overdose and his dad to drug psychosis. There were so many creepy medicine men and missionaries on the Rez that he, like many of of my students, was highly suspicious of anything spiritual or religious. When I found out what had happened to his parents, I lost my ability to stand in front of him during the day and then journey with the shaman’s questionable little white pills at night. Plus, Zoom journeys creeped me out. The shaman was becoming too much like Lawnmower Man, and then he called me out on Zoom, claiming he had been trying to protect me from the Rez and, apparently, my fate.

So, on New Year’s Eve of 2021, I cut ties with the shaman.

Then the abyss opened its arms to me. I didn’t see the difference between me and my students’ parents, except that I was white and I’d had access to designer drugs and therapy groups, while they had fettys and drug cartels. I’d lost my connection to my nascent spirituality, and, because of the shaman’s grooming, I was no longer so sure about reality. I was living in a tiny apartment on the Rez and isolated from everyone who cared about me. For the first time in my life, I experienced suicidal ideation.

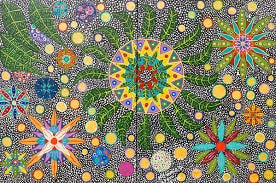

I made it through that winter by watching Rez ball. It inspired me to watch kids who had lost their parents and been bullied their whole lives become extraordinary on the court. Despite the nasty politics in the school, despite the blatant racism of referees on the Hi-Line, despite the hits they took for standing out, these kids kept getting bigger and bigger. When I asked him how he did it, the Rez baller in my class shrugged and said, “Storey, haters gonna hate.” Him and his teammates threw the type of no-look passes I’d never seen a kid even attempt in the six years I taught at a white school in southern Montana, and they nailed half-court hail Marys with such regularity that I couldn’t believe colleges would barely look at them. They came back from 20-point deficits like it was part of their plan. The Rez baller in my class could fleece a steal anytime he felt like it and hit a fadeaway—the hardest shot—like clockwork. He got more three-point conversions and forced more turnovers than I’d ever seen in high school ball. It was thrilling. It was unreal; it was psychedelic. Basketball became the realest thing to me, a way I could still see magic in the world, even without the shaman and his drugs.

Meanwhile, the heat didn’t work in my classroom and we went almost a month without water. Meanwhile, the kids were still working out with hand-held weights and resistance bands in gym class even though they’d been asking for a weight room for years and the school had millions of dollars. Meanwhile, people were dying or turning up missing and the cartels were moving into all the Reservations in Montana.

I started to feel like no one knew me like those Rez kids, so in 2022, I came out to my students as a drug user. The baller looked at the student sitting next to him—with whom he played online chess—and said, “I told you so.”

Then, to the whole class, he said, “Storey, you were in a cult.”

I tried to argue with him, but after I quit teaching I researched his statement and I learned he was right: Because of suggestibility and limerence, psychedelics easily and effectively create cult dynamics, which were certainly present in my teacher’s group.

After he told me I had been in a cult, the baller asked me another question I couldn’t answer. He was like, “What drugs did you do?”

The rest of the class chimed in. They were all curious about the drugs. But I couldn’t answer them fully because even I didn’t know what drugs I had done. Sometimes I just ate whatever pill the shaman gave me. Once I was in a group in which the facilitator made us choose pills intuitively from her fanny pack, which meant you closed your eyes and rifled around in there until your fingers snatched one.

I always hated writing essential questions for lessons plans, so I found it fitting that my teaching career ended with a student asking me a few. I’ve spent the last two years trying to answer that kid’s questions. The exploration produced my novel, The Shaman’s Wives, and this newsletter.